GEOMETRY SCHOOL: HEAD-ON WITH HEAD ANGLES

Is slacker always better?

One of the biggest advancements in mountain biking in the last decade has happened with geometry. Generally speaking, bikes have gotten longer, slacker and lower. As a result they are far easier to ride, particularly on the downhills. Want proof? Just throw a leg over a 10-year-old bike and compare it to a new one. Geometry is incredibly complex because one thing often affects others. And, painting a bike with a broad brushstroke because it has a certain number is a mistake we hear some riders make. Yet there are things that can be learned about what each number means and how it can affect a bike’s ride.

In this series on geometry, we start at the front of the bike and focus solely on the head angle. Here at MBA we know a lot about bikes and even geometry, but not as much as the folks who design them. So, we reached out to Josh Kissner (Santa Cruz Bicycles’ senior product manager) and Colin Hughes (engineering manager at Ibis Cycles) to get their take on mountain bike head angles and where they’re going. One of the most commonly used marketing terms over the last decade has been calling every bike “slacker, lower and longer.” For the most part, that was, and still is, true, but things can’t keep going in that direction forever, and there are signs that these geometry trends are starting to plateau.

Photo courtesy of Ibis

SIMPLE YET COMPLEX

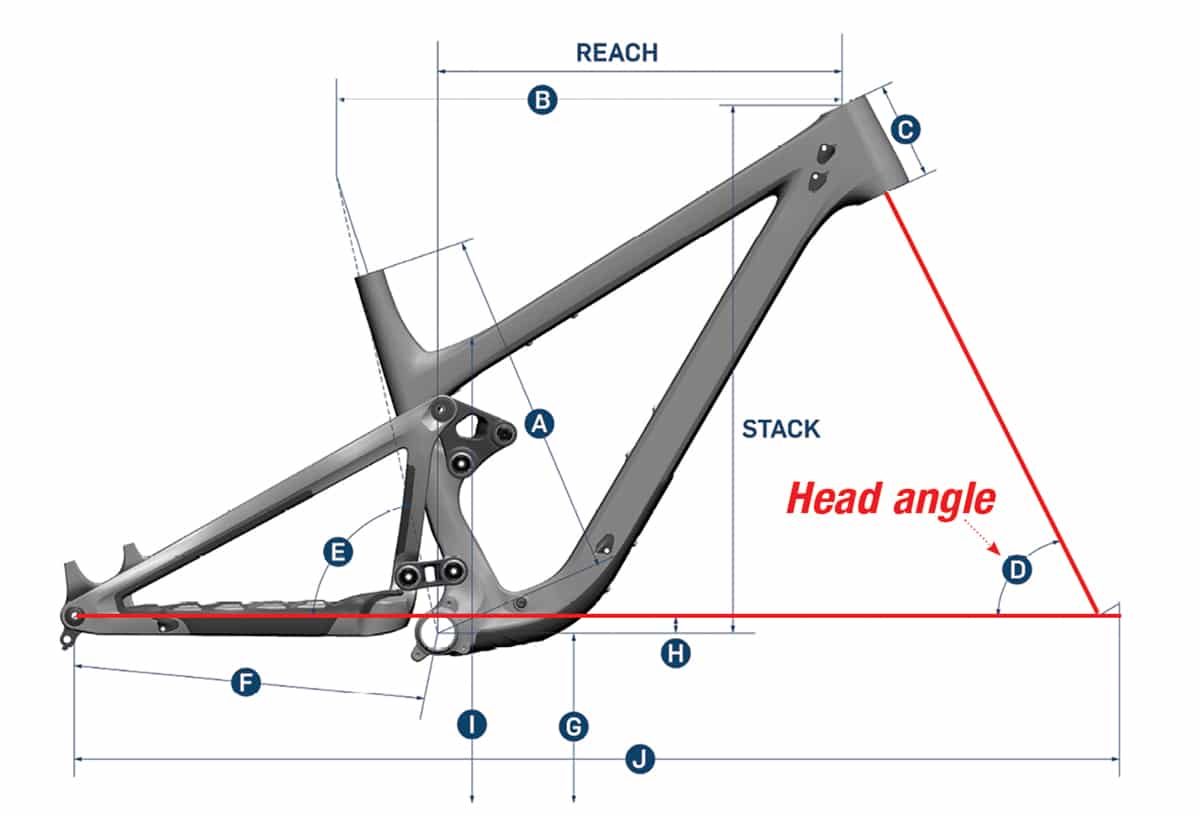

The head angle is the angle of the head tube in relation to the ground. Generally speaking, steep head angles offer steering that is light and quick, while slack head angles are slower and more stable. The term “steep” goes with values such as 71 degrees, while the word “slack” corresponds to a lower number like 62 degrees. Head angles are just part of the steering puzzle, though. Hughes says that you also need to know the trail measurement, stack, reach, chainstay length, bottom bracket height, stem length, bar width and how some of those things change at sag to really know how a bike rides.

Kissner concurs: “There’s certainly a lot happening with bike geometry at the moment, and head angle is only one piece of the puzzle. It’s an important piece of information, but it is most useful in the context of the rest of the geometry chart—plus wheel size, suspension kinematics and such factors.

In fact, you can’t really talk about the head angle’s effect on steering without going down the trail rabbit hole. “We don’t think solely in terms of head angle and actually use a measurement called trail,” says Hughes. “Trail is the distance that the front tire’s contact patch sits behind the steering axis. The further back, the more stable the steering will be. We know what that number needs to be for different types of riding.”

That’s right—bike manufacturers know what trail numbers are ideal for certain types of riding, and adjusting the head angle is one way to get it. Another is fork offset. “Fork offset is one of the variables in the trail calculation,” says Hughes. “Less fork offset gives more trail. So, a short offset fork makes the bike more stable without having to make the head angle even slacker.” By manipulating fork offset and moving that vertical axis of the front axle and tire contact patch forward or backward, you can change the bike’s trail. Yet, another variable that affects trail is wheel diameter. “A larger-diameter wheel will give a larger trail number, and the head angle does not need to be as steep to give the same feeling,” says Hughes.

“The other major effect it has is front-center length, which is the distance between the bottom bracket and the front wheel,” says Kissner. “A slacker head angle will situate the front wheel further in front of the rider, adding stability and decreasing the chances of going over the bars.”

Photo by: Ben Haggar

HOW IT’S MADE

As you can see, there are many variables that head angle affects and vice versa. So, how do frame designers figure out the ideal head angle for the bike they are designing? “We start with a plan based on prior bikes and an understanding of how we’d like the new one to differ,” says Kissner. “We then make prototype ‘mules’ in-house to test our planned geometry and suspension kinematics, and then can make an informed final decision after spending some months riding those.”

One more thing manufacturers do that affects the head angle is at the opposite end of the bike, and that’s the rear suspension. When a rider is braking, the weight transfers to the front end as the fork compresses and the rear suspension extends. As a result, the head angle gets steeper, and not always when you want it to. Engineers can tune anti-rise into the rear suspension so that when a rider is braking, the position of the back end stays neutral (or even slightly lower) to make the bike more predictable.

CHANGING IT UP

Head angles are not necessarily fixed. Some bikes can utilize angle sets with offset cups to change the head angle. Kissner says that angle sets were a commonly used tool to “fix” the geometry of bikes a few years ago and can still be useful today to breathe new life into older bikes. “Most modern bikes are probably slack enough at this point, but it still varies for sure,” he adds. “We use them on our mules to experiment, and riders can do the same on their own bikes if they feel a need.” Ibis also uses them to check geometry as they develop new models.

These adjustable headsets come in a variety of styles, but Cane Creek’s AngleSet was one of the first, and it uses a combination of offset cups and conical bearing seats that they call a “gimbal system” that self-aligns. The AngelSet allows users to steepen or slacken the head angle by either .5, 1, or 1.5 degrees. The downside to this type of angle set is that they tend to creak because of the unfixed bearing seats. Others such as Wolf Tooth, Works Components and 9point8 use cups with angled bearing seats but are head-tube-length-specific. According to Wolf Tooth, the maker of the GeoShift angle headset, 1 degree of head angle adjustment results in a 5–7-percent change in handling.

Photo by Bartek Wolinski / Red Bull Content Pool

We are seeing more bikes like the Specialized Stumpjumper EVO come with adjustable headset cups as part of their design. When we tested that bike and all of the head angle settings, we found that a particular stem length was required to maintain neutral steering. “Shorter stems will make steering quicker and will moderate a slack head angle and/or short-offset fork,” Kissner says. “The combination of short stems (and the long reach that goes with them) and a slack head angle add stability and length to the bike while keeping it from feeling like a bus. A slack head angle combined with a long stem and short offset fork would be a real bummer to turn. Add in a very wide bar and the bike will pretty much just want to go straight.” Kissner adds that modern geometry (slack head angle included) is optimized for short stems. This means that the reach is pretty critical, and riders should make sure the fit of a new bike will work with the stock stem size or one very similar.

Kissner says that the other thing to consider is the chainstay length and how it compares to the front-center length, which is highly influenced by head angle. Bikes can get pretty weird with very long front ends and very short rear ends, or vice versa, he says. Head angle changes can affect bike fit to a small degree. “I think in terms of front-center/wheelbase, it does affect fit a bit,” says Kissner. “Riders on downhill bikes often look at wheelbase length, in addition to reach and stack, to figure out how a bike will ride. To a lesser degree, a slack head angle can shorten the effective reach of a bike if a lot of headset spacers are under the stem.” Hughes says that to make a slack head tube angle work, you’re probably going to want a steeper seat tube angle, too. That’s going to move everything forward so your body position will change.

Photo by Trevor Lyden

WHERE ARE THINGS HEADING?

Back in the early ’90s, it was common for mountain bikes to have a 71-degree head angle, give or take a degree. Over time we have slowly seen head angles get slacker even on cross-country race bikes. For example, the new Cannondale Scalpel HT hardtail now sports a 67-degree head angle. “Back in the ’90s, XC was the dominant form of riding, so there was a focus on making bikes climb really well,” Hughes explains. “Steep head angles keep the front wheel closer to the rider. That keeps some weight on it during steep climbs, allowing the rider to steer. Now we make the seat tube angle steep to position the rider more forward instead. The other thing that happened since the ’90s is that suspension got a lot better. That allows riders to go faster, so they need more stability.”

Photo by Red Bull Content Pool

Kissner says that bikes have evolved to be very different from the bikes of the ’90s, and these changes all feed into each other. “Improved suspension allows for faster riding, which encourages improved brakes, tires and larger wheels to keep up,” he says. “Dropper posts allow riders to corner in a totally different way than we used to, which allows for more stable bikes. As the above components have improved, bike geometry has changed alongside them. This organic shift over time keeps improving on the weak link in the system, so everything is harmonized.”

So, with bikes coming with more relaxed head angles with seemingly every model iteration, where is the limit on slack head angles? Hughes thinks that it depends on the terrain and type of riding, but for most people, it seems like we might be there. “Downhill bikes have settled around 62 degrees, and enduro around 64 degrees,” he says. “In order to make a head angle slacker on anything but a pure downhill bike, you need to make the seat angle steeper to keep some weight on the wheel. I’m not sure we can go much steeper with the seat angles.”

Kissner says, “Who knows? It certainly feels like we’re close, with modern enduro bikes now sitting in the 63.5-degree realm. Much slacker than that and forks struggle to absorb bumps properly, and the bike becomes a one-trick pony for very steep descents only. I won’t claim to know what happens in the future, but it feels like we’re getting close to the edge.”