THE UNOFFICIAL HISTORY OF CANNONDALE (ACCORDING TO SOMEONE WHO WAS THERE)

Born into the American brand, Scott Montgomery looks back on five decades of aluminum fun

By Zap

The year was 1993, and I was headed to Sun Valley, Idaho, for the exclusive first ride of a new Cannondale called the Super V. I knew nothing about the bike, nor anything about the guy who was flying in to ride with me. His name was Scott Montgomery, and his dad was Joe Montgomery, the founder of Cannondale bicycles. Over the course of a few days we rode, crashed, talked about bikes and got to know one another. I‘m happy to say that our friendship has continued to this day.

I’ll admit that Cannondale is one brand I think very fondly of, and that’s the result of the respect I have for company founder Joe Montgomery and the litany of people who worked for the brand over the years. Known early on for a mixed-wheel bike, the SM400 (26-inch front/24-inch rear), the then-American-made bikes first entered my life in a test we did of a Mint Green (with pink splotches) SM900 back in 1987. Next came a quick test ride of the SE rear suspension bike at the 1990 Durango Worlds that stood out for its Lime Green color scheme, elevated rear triangle and Girven Flex stem.

All those early-tech and fashion miscues aside, it was in 1994 with the formation of the Volvo-Cannondale team that the brand really caught on for me. This was a team that became world famous for an eight-year span and was home to some of the greatest riders the sport has ever known.

THE UPS AND DOWNS

As the history books recount, Cannondale made its name with aluminum-tubed bikes crafted in its Bedford, Pennsylvania, factory. Of the many things the brand was famous for, there were some distinct moments that shaped its later history. In 1995, the company went public. The year 1997 saw the debut of both the radical Fulcrum DH bike and the carbon Raven, which was the brand’s first non-aluminum bike. The Cannondale motorcycle was also born in 1997, and in 2003 the company filed for bankruptcy. Finally, in 2014, Cannondale ceased being an American manufacturer when the Bedford plant was closed and all frame manufacturing was moved to Asia. Most recently, the Canadian investment group Questor sold Cannondale (as part of a group sale along with GT, Schwinn and Mongoose) to the Dutch Pon group

I still remember the moment at the 1997 Indianapolis Motorcycle show when Cannondale made its official debut in the motorcycle world. There was Joe Montgomery, slender and casually well-dressed as always, talking up the promise of this incredibly bold departure for his bicycle company. And just as he departed the elevated stage after unveiling the bike, he tripped and almost came crashing to the ground. Little did I know then how prophetic that moment would prove, as the motocross venture that seemed to hold so much promise would eventually cause Joe to lose control of his company.

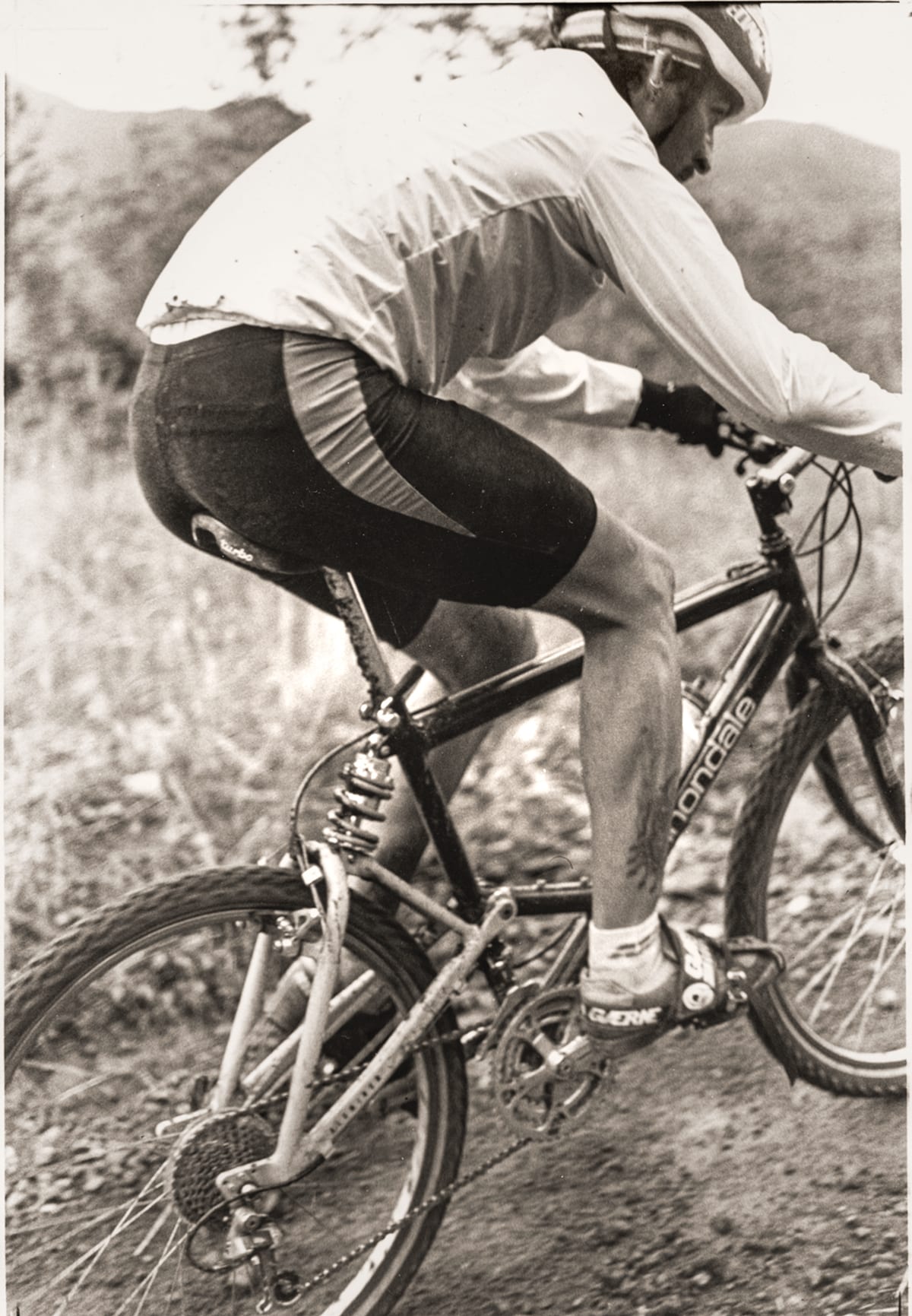

Photo by Zap

THE SCION SPEAKS

When did you first become aware of your dad’s plan to start a bike company?

It was 1971 and the 10-speed boom was getting more people riding on the roads and touring. There were three employees. A lot of people don’t know that Cannondale started out as a bike trailer company with the aluminum Bugger. Then we quickly moved to making bike bags for people who were touring.

When did you begin to get involved in the business?

My first working days were when I was 11. I would work at Cannondale when I was out of school for breaks. I helped assemble the seat bags, stuffing in the foam inner liners and attaching the buckles and header cards. One time I was told to help with inventory. There was this massive barrel of steel J-hooks, and I was told to count them, one at a time. You can imagine that kept me busy for the better part of a few weeks, and I am sure the counts were way less accurate than just weighing 100 pieces and then weighing the barrel, but it kept the boss’ kid busy and out of the way.

You later played a role in getting Cannondale overseas.

Well, in 1987, we were losing quite a bit of money, even though we were growing quickly. It was due to typical growth issues and a bunch of young inexperienced people (like me) doing big jobs. My father called me into his office one evening, which was pretty common, and said, “How would you like to move to Europe?” I said I would love to. The next day I bought a ticket and was off to the Netherlands with a few ties and a cheap inherited suit, and we started Cannondale Europe. Three years later he asked me about Japan. I again said, “Bring it on,” and headed to a Tokyo trade show in search of figuring it out.

Was there an early period when Cannondale got “serious” in terms of business strategies?

Certainly 1992 was a big, big year. We had built Cannondale Europe, which was growing like crazy, as we were way ahead of the big European brands in bringing the mountain bike to market. Then we added front suspension, and finally we introduced the full-suspension bike, which was almost unrideable, but it positioned our brand as way ahead of the curve, and we sold a ton of front and non-suspended mountain bikes. The profits that came from Europe fueled the hiring of some professional staff and enabled us to raise private equity money to fuel our growth, and that is when we really had the volume and scale to start to become excellent manufacturers, which in turn increased sales and margins.

What was the first “hit” in terms of Cannondale models?

Well, the first road bikes were light, about 3 pounds for an alloy frame versus 4 pounds for an Italian or French steel frame. I will say at first it was not a “hit.” It was more of a “dentist bike” for nerdy, smart, technical men who wanted to be different. I remember being in a 10×20 booth at a NY trade show around 1984, and most of the dealers who walked by felt sorry for us more than anything else. Sort of reminds me of Tesla. At first it was considered a dorky product, only later would we become hot!

I still recall the “Beast from the East” with the 24-inch rear wheel. What were Cannondale’s early notions about mountain biking?

We had a bunch of fun making that bike. Since we were eastern-based, we had lots of roots, logs and wet trails, so the bike needed ample ground clearance, and it had a really high BB to assist with that style of riding. Of course, the cool guys riding out west thought it was a stupid idea. It got us on the map, but we did not sell many mountain bikes in the west prior to 1990.

Photo by Mike Koger

What was the idea behind “systems technology,” and what compelled you to develop your own suspension?

My father and Mario Galasso (later known as one of the key leaders of Fox Shox following his Cannondale days) wanted to be independent of the key suppliers like Manitou and RockShox, so we figured if we built both the frame and suspension and key parts like disc brakes, tires and stems, it would help differentiate us. What it really did was make us more money, because when we introduced a CODA crank to replace a Shimano crank, we purchased them at a 15-percent better price, which all dropped to the bottom line and in turn funded more R&D spending to increase more investment, mostly in suspension and frame technologies.

Cannondale had been into racing, but it really exploded with the Volvo deal. How and when did that relationship begin?

While I was in Japan, we had created the New Balance-Cannondale team, which was the idea of Michael Jackson and Wink Zimick; it was our first real race team effort. The marketing department had guys like me going to races each weekend. We grew our sales, and we got the sub-sponsors to pay for most of the bill. After my six years abroad, I was ready to return to America and start raising a family. So, I pitched the idea to my father of creating a big global mountain bike racing team. He loved the idea, with one caveat, “It has to be 100 percent self-funded.”

Photo courtesy of Cannondale

I left his office deflated but went to work. Dick Resch, who was our COO, gave me the contact for someone he had met at Volvo. I called him up and pitched him on the idea of the Volvo-Cannondale racing team. At first, he wanted to call it the Volvo team, but after he and I went to Hyannis to the Kennedy-sponsored Buddies ride, I somehow convinced him that a Volvo-Cannondale team would make Volvo cooler, as they were a little bit of a dorky “safety/dentist” brand themselves at the time. On the way home, he turned to me and said, “After riding with all these cyclists this weekend, I think you are right.” And the rest is history.

What role did racing play for Cannondale?

I’d have to say that all our in-house work aside, racing is what made the difference for the brand. I remember back in 1994 when the team came by the office on the way to Mt. Snow for a meeting, and I thought it was going to be a love fest. It wasn’t! Missy railed against the bikes, and even mild-mannered Tinker sounded off. I realized quickly that I was losing control of the meeting and went to get Mario and my dad to hear from the riders first-hand. The pay-off was great, because instead of all the in-house ideas we heard, it came down to the team telling us what they needed to win, and there was no bureaucracy involved.

Racing is still important, and it’s what keeps the polish on any bike brand. Although the return on investment isn’t what it was back in the ’90s, you can’t expect consumers to ride the bikes as hard as the pros, so that’s where the real value of spending money competing comes from.

There was a time when people took digs at our aluminum frames and called them “Crack & Fails,” but by investing in better testing, hiring certified welders and winning so many races, we proved the bikes could last and all the name calling stopped. It was no different on the road. The Europeans laughed when we started the Saeco team, because no one rode aluminum bikes over there. But, the next thing you know, we were winning stages in the Tour de France! The thing is, you can’t expect consumers to ride the bikes as hard as the pros do, so that’s where the real value of spending money on racing comes from.

How did the crazy Fulcrum DH bike come into being?

You know, of all the bikes we did, I might be most proud of that one, because it was the clearest example of a clean-sheet design. Again, we’d heard from the racers about what they needed, and that bike reflected our approach of trying to come up with something for the world’s best riders to win on. We knew that if it didn’t work, we’d move on.

Was there a big difference between dealing with the cross-country and downhill riders?

For sure. Obviously, there was a lot less technology involved in the cross-country bikes, but they were the ones that we sold the most of, so it was important to stay on top of what Tinker, Alison Sydor and Cadel Evans needed. The downhill riders definitely pushed us harder, like when Myles was asking for 160mm of travel when everything only got 60mm! And yeah, I remember having to deal with “Cryin’” Brian Lopes a lot, but it wasn’t because he wasn’t right; he was just pushing the technology. The riders wanted to win—and so did we!

What is your favorite Missy Giove story (that we can print!)?

Wow, there are so many stories there. Well, there was the Worlds in Vail in ’94. Missy was expected to be in the top five, so this photographer from Sports Illustrated came out and two days before the race he had all the expected winners ride the same section of the course, riding super slow, and took a bazillion pictures. Then, he left.

At that time, Missy refused to ride the current HeadShok because the travel was limited to 45mm. And remember, this is a DH race, so she said, “Either I ride the Rock Shox (which had about 75mm of travel) or I’m not going to race.” Of course, this was completely against the rules of her contract, and I was there with our team manager, Tom Schuler. We didn’t know what to do! I told Tom, “I can’t tell my father this or he is going to go ballistic!”

So, I made the decision to let her ride with the Rock Shox and, of course, she won. There was a two-page spread in Sports Illustrated, which at the time was worth about $100k, and a few keen readers probably noticed the Rock Shox, sans stickers (which I took off), but no one cared because the gigantic yellow Cannondale on the downtube was all anyone remembered. Eventually, we built some pretty good inverted suspension forks for the team, but that all came later.

Did Cannondale ever consider making bikes in steel or titanium?

Never, not for a minute. David Graham was working for Electric Boat, which built submarines for the Navy, and he wrote my father this two-page letter about how a fat-tubed aluminum frame would be lighter and stronger than a steel frame. My fath

er called him the next day, hired him in ’81, and 24 months later in early ’84, Cannondale started with a fat-tube 6061-T6 touring frame.

From wheelchairs to motorcycles: what was the motivation to diversify?

We had gone public, and the pressure to keep growing was immense. We had a pretty strong balance sheet from two rounds of stock sales. We had money to burn. The wheelchair stemmed from the fact that my brother Michael had CP and was in a wheelchair, so it was a personal passion and just felt great, as the chairs that many Vietnam veterans were using at that time were junk.

The moto project is a long story and was just us swinging for the fences. We tried to take on Honda and Yamaha with $100 million, but it was at least a $500 million project, so basically, we way underestimated the cash we would need. And, of course, toss into the middle of that the awful 9/11 catastrophe, which started a recession and killed off additional capital raises, which led to the Chapter 11 filing and closure of the moto division.

How did Cannondale gauge the need for going public? What drove that decision?

We had taken a private equity investment from a group within Morgan Stanley called Princess Gate. It was a fund with about $500 million from the super-wealthy clients at Morgan Stanley who were willing to put $5–$10 million in riskier investments for high returns. The original deal invested $10 million in the company for a small stake with a high-interest rate coupon on the cash, which further increased the return on investment because the lenders made money on both the interest and the increase in share value. Anyway, these deals happen all day long and have a term of generally five years, where the outcome is either go public, sell to a bigger firm, or go bankrupt.

Eventually, the fund owned about 1/3 of the company, because they had lent us more money to keep up exceptionally high growth. I had things rolling in Europe and now Asia, and, of course, we were getting hot, especially in the mountain bike world with full suspension, so we needed capital to fund the growth at high levels. Basically, the time was upon us to either sell the company or go public. We chose going public, which was great for investors and employees. Overnight, our debt went to almost nothing, and we had a pot of gold to grow even further.

There was quite a bit of industry ruckus when brands like Cannondale and RockShox went public.

Well, for us, it was not a choice. We either had to go public or sell the company. So, in the short term, it was fantastic. It reduced our interest expense dramatically, because the high debt with high interest rate went to almost nothing. We continued to grow quickly, and we could take that seven-figure interest rate expense and put it into much more exciting places like R&D, race teams, marketing, and hiring more smart and experienced staff. I think for Paul at Rock Shox it was similar, or for Richard Long of GT the same.

At the time, the market was hot and growing, and shareholders saw the opportunity to cash out. It is not too dissimilar to what is going on today in the market with many companies changing hands. Just today, Jake sold Kona. Selle Royal is planning to go public. At the end of the day, we build bikes out of passion, but there is big money on the line. At some point, the man has to be paid back for the money the shareholders have invested along the way.

How would you describe the U.S. mountain bike boom in the ’90s?

That was wild and exciting. The growth was explosive, and it gave all the American brands a chance to grow and enter Europe and Asia. I remember sitting in the fourth-floor office with our Dutch bank talking about how we were going to sell all these light aluminum mountain bikes. The Dutch banker was this crusty old guy who was smoking a stinkin’ cigar in our meeting. After listening to (Cannondale co-founder) Scott Bell and I talk about why he needed to lend us what was about $200,000 at the time, he told us to go pound sand and said the Netherlands producers knew more about bicycles on one finger than we knew in total, which was right.

Anyway, I was young and stupid, and as we exited the conference room, I got my face about 6 inches away from his cigar breath and said, “Listen, this is a true innovation, and you need to give us a chance.” For some reason, he gave us a small line of credit. I was very happy when a few years later he could no longer sign off on our loans because they were over $10 million, which required his boss in Amsterdam to approve. That made me smile.

What’s your version of our ’93 meet-up in Sun Valley with the Super V?

There was this discussion going on inside Cannondale about why we never got good reviews from MBA. We pretty much thought it was because you guys were just way “too cool for school” Cali boys, and we were a bunch of dorks from Connecticut with wet trails with roots and bikes that did not ride well on the dry dirt out west. At the time, we were too broke to travel to California to test our bikes anyway. Fast forward, and we had the Super V coming out, and I was now in Japan, having started Cannondale Japan. The sourcing trading company and I got wind that no one wanted to show MBA the Super V, and I went nuts.

I think a lot of the guys were scared of you and MBA, and they all wanted the bike reviewed by Bicycling. But, since we were already well-regarded by them, this was the time to work with MBA. If we were cool with you guys, it would help us get out of the “Dentist Bike” East Coast vibe and really start to become a player in mountain bikes. I told my father I would handle the issue and invited you to Sun Valley, Idaho, to ride the bike with Mark Farris, who designed the Super V. And, if I recall, you guys liked the bike and that was it.

Looking back, what role in the sport did Cannondale play?

I think we were a good East Coast counter to the sport’s early West Coast influence and preference. Don’t forget how many people who came up through Cannondale and went on to play significant roles developing new technology with other brands.

In the end, Cannondale was among a league of elite competitors, like Specialized, Trek, GT and Giant, who were each fighting hard to be better than their competition. Great competition breeds good products, and, in the end, it was the consumers who benefited the most from our desire to beat one another. In fact, I think it was the industry competitiveness between my dad, the Burkes and Sinyard back in the ’90s that created a legacy for many brands to be just as competitive and dedicated to developing great products today.

Okay, enough about the bike industry. What does the mountain bike mean to you?

When I started out with Cannondale, it wasn’t about the bike but the business that I thought about most. Now, not a day goes by that I’m not thinking about riding or actually riding. Mountain biking is just so fun. I mean, there you are in the great outdoors, sweating as you pedal up the mountain and giggling on the way back down—that’s a hard combination to beat!